Why Rounded Schoolhouse Does Not Grade Student Work

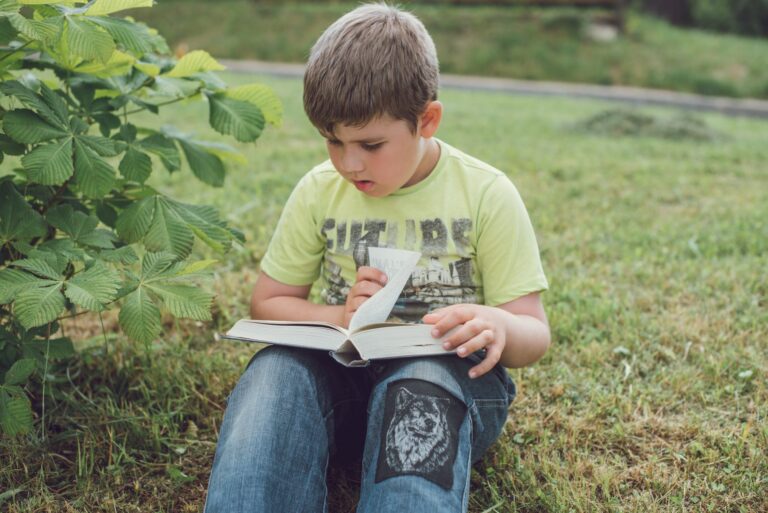

One of the most common questions we get about Rounded Schoolhouse is “how does grading work?” The answer is usually surprising.

This is a controversial topic and I know parents land on both sides. I have no contempt for parents who prefer grading throughout the semester for their students. You are the parent and that’s entirely your prerogative. This post is only about why Rounded Schoolhouse does not grade work.

First, those folks that ask about grading usually have an expectation that grading is always part of a student’s school experience. Daily scores. Scores for each assignment. Scores for quizzes. Scores for tests. Scores for projects. Averaged scores.

And all those scores coalesced, averaged, and weighted to form a single letter: A, B, C, D, or F.

I don’t blame any parent for expecting grades to be a part of their student’s learning experience. We were all raised with grades at every step of our schooling.

I remember being so proud of every A and B I earned, though I wouldn’t say it was the majority of my grades. I’d strut home 10 feet tall to show my mom my slightly above average report card. I knew pizza or ice cream would be my reward for 9 weeks of hard work.

I also remember the dread of getting a quiz back that I felt unprepared for. I can still feel the anxiety of it. The teacher walking from desk to desk, handing out graded quizzes and little Scott hoping (PRAYING) that she wouldn’t place my quiz on my desk face down. We all know what a face-down quiz means…

You probably remember the time-honored ritual of taking your report card home to your parents. Maybe you contemplated how you could change your F to a B with a little careful editing on the bus ride home. Or maybe you were a fantastic student and never worried about that “school talk” at home.

In either case, grades were a large part of our school experience, for better or worse.

Grades May Not Be Useful, Potentially Harmful

Grades are an efficient way of quantifying the performance of large groups of children. But, on an individual basis, grades may not be useful or helpful. In fact, in some ways grades can be harmful.

-

Grades have become the end goal despite their lack of usefulness in predicting adult job performance. There is little-to-no correlation between GPA and job performance. Google’s former Senior Vice President of People Operations, Laszlo Bock, says, “GPA scores are worthless as a criteria for hiring, they do not predict anything.”

-

Grades are a poor form of feedback. Einstein once said, “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.”

-

Grades create risk-averse behavior. They encourage rote performance, not creative or risky approaches to learning. In projects, they foster a least-risk-approach to ensure a good grade rather than the best potential outcome. Dutch designer and THNKer Marcel Wanders once argued in a THNK session: “Doing a good project in school should be forbidden…students have to make as many mistakes as possible, and learn from it.”

-

Grades risk skewing a child’s sense of self-worth. A 2002 psychology study found that over 80% of college freshmen based their self-worth on academic competence—more than family support, appearance, or any other single factor.

-

Grades shift learning from intrinsic to extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation, sometimes called inward motivational orientation, is motivation that is “self-[centered] in a positive way,” in that someone’s own “desire to learn from the task has the highest priority.” Extrinsic motivation, on the other hand, relies entirely on the outside world for incentives, such as praise and grades, to learn.

-

Grades do not provide descriptive feedback on performance. From one study: “Providing evaluative feedback (in this case, grades) after a task does not appear to enhance students’ future performance in problem-solving.” Students who received descriptive feedback, on the other hand, performed significantly better on all subsequent tasks than students in the other two groups. In fact, evaluative feedback not only doesn’t help students perform better in the future, it often distracts students from absorbing important descriptive feedback in the present.

Choosing A Different Way

One of the beautiful things about homeschooling is we, the parents, get to choose a different way for our kids. When we choose a different way, it doesn’t mean that all other ways are wrong.

It just means that this way is the right way for me and my family.

When it comes to grading, many homeschool parents still believe it is necessary to gauge the progress of their child. Grading, after all, is how we measure learning, right?

It is one way, but it’s not the only way.

Even in public/private schools, learning is measured in other ways: attendance, group participation, projects, work completed, etc.

At Rounded Schoolhouse, we’ve chosen a different way than using grades as the measure of student progress…and it’s exceedingly simple.

We don’t grade assignments in the traditional sense. Assignments, quizzes, and other work is simply marked as complete. Completeness, then, is the measure of progress.

There are assignments that require a human touch to evaluate performance. Writing assignments, projects, worksheets, and more all require a human to provide descriptive feedback. In our system, the parent is responsible for providing that descriptive feedback.

Why the parent? Because the parent already provides descriptive feedback in every other area of the student’s life. The parent tells their child if their room is clean enough and, if not, then what to do differently to achieve the desired result. The parent doesn’t give a student a grade on their clean room. No one tracks their room-cleanliness-GPA year-over-year.

Rounded Schoolhouse is designed to let the parent be the parent. Check work. Decide if that work meets your child’s level of ability. Consider what type of feedback your child needs to either feel good about their work or to improve in some way.

We believe in parents. While not every parent is perfectly equipped to be their child’s primary teacher, every parent is perfectly equipped to provide this kind of descriptive feedback.